1. Define challenges

Prioritizing tertiary education for hard-to-reach refugees

Education is a core component of UNHCR´s mandate to protect 31.7 million uprooted people worldwide, and a key element supporting sustainable development. The agency´s education strategy highlights the importance of learning outcomes and making lifelong learning accessible for all, from early childhood education to secondary, higher and adult education.

Indeed, tertiary education — which includes all types of post-secondary education, degree programs and para-professional certified trainings — enhances the protection of youth and facilitates integration by placing refugees at equal footing with non-refugee youth.

UNHCR and its partners have long worked to integrate refugees into local education systems. But that´s not always feasible due to host country restrictions. Even if a country is willing to integrate refugees, a lack of resources can limit its ability to absorb students into existing systems. There also is a dearth of qualified teachers in refugee contexts, which limits the community´s ability to graduate through the educational continuum.

At times, the mere availability of education opportunities can upset local power dynamics and exacerbate conflict. Certificates that are attained are often not recognized or seen as relevant in either the refugee´s host country or country of origin. It´s one reason why UNHCR administers the Albert Einstein German Academic Refugee Initiative, which has supported tertiary education for refugees worldwide since 1992.

The program, also known as DAFI, helped more than 2,200 students across 42 host countries to attend university in 2014. Many more applied, though: Unfortunately, the high per-student cost of traditional scholarship programs like DAFI limits their scalability. At the same time, relocation is not feasible for all refugees, especially those with families or responsibilities in the camps they live in.

2. Identify solutions

Overcoming distance and time to connect refugees to learning through ICT

Given the large number of refugee students seeking tertiary education, their lack of resources, insufficient opportunities in-country, the geographic isolation of camp-based refugees and their sometimes restricted mobility, UNHCR and its partners have been eager to ramp up distance and virtual learning.

The U.N. Refugee Agency has adopted the term “connected learning” to highlight the benefits of educational programs that connect refugees and marginalized populations to accredited academic institutions and mentors. A key part of UNHCR´s strategy is to encourage access to certified higher education courses through partnerships with academic institutions and others with technical expertise in this area.

Through the use of information communication technology, connected learning enables learning that is not bound by the same time and geographical limitations which exist within traditional tertiary programs. Connected learning programs tend to use a mix of face-to-face and digital interactions with instructors or tutors, and they employ a variety of tech components such as the Internet, video, CDs and DVDs, mobile phones and printed materials.

The flexibility connected learning brings is particularly relevant for refugee students. These programs often don´t have age limits for learners. They allow students more time to complete courses. And they give learners the chance to study from their current location — a fact that is particularly relevant for female students and those with special needs.

UNHCR sought to expand access to connected learning opportunities for refugee students, and it didn´t take long to identify partners with experience in this realm.

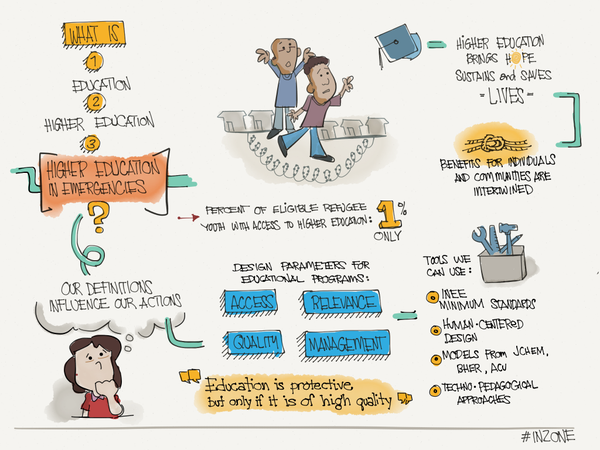

Higher education helps refugees find jobs and sustain a dignified lifestyle.

Illustration credit to Ed Guzman.

3. Test solutions

Crafting guidelines and a know-how framework for distance learning with participating institutions

In February 2014, UNHCR hosted a roundtable in Nairobi, Kenya, on connected higher learning programs for refugees. Participants recognized the need for active collaboration between different actors, including foundations, businesses and other entities, each of which brings a unique set expertise and resources to the table.

To facilitate collaboration, UNHCR agreed to work with partners like Jesuit Commons Higher Education at the Margins to develop a framework for connected learning programs. The agency also pledged to urge universities and other post-secondary institutions to support connected learning programs.

Since the meeting, UNHCR has facilitated the sharing of information and best practices among partners like the Australian Catholic University and the African Virtual University, which has been developing open-source courses. InZone has used its techno-pedagogical know-how and field experience to craft best practice guidelines for distance learning and open courseware that allows refugee learners to reach their higher education objectives.

The Borderless Higher Education for Refugee Project, meanwhile, has been working with partners to engender the development and sustainability of connected learning.

The Swiss Humanitarian Organization, a new actor in this area, proposed to pilot the design and construction of a new learning space adapted to connected learning needs in camps. It also pledged to identify partners in Africa and in the Middle East, and to advocate for the Sorbonne to sponsor students from refugee camps.

4. Refine solutions

Building a consortium to invest in connected learning

UNHCR and its partners quickly realized that a consortium of academic and humanitarian actors is vital for ensuring effective and sustainable connected learning programs. While the role of each actor differs from program to program, UNHCR tends to be responsible for ensuring a program is aligned with its humanitarian protection mandate while universities and other educational institutions advocate in-house for refugee-focused programs and ensure that content and pedagogy of virtual learning align with international academic standards.

The partners have drawn many important lessons from their work, including on the importance of adapting pedagogical tools and strategies to different cultures of learning, managing students´ expectations and supporting people with limited verbal or written abilities.

While the flexibility of studying at school or at home has been deemed important — and, in the case of technological challenges, cultural considerations and environment-caused delays, crucial — partners also recognized the importance of having learning hubs in central spaces that allow for students to come together as a community of learners.

A continuing challenge lies in the need to preserve the quality of education while respecting inclusion: Concerns have been raised, for instance, that lowering the entry grade required for admission into connected learning programs could compromise the program´s academic validity.

Partnerships with local institutions may facilitate more culturally relevant strategies, but connected learning actors also agreed on the need to invest in global approaches and encourage universities around the world to play a more active role in providing higher education opportunities for persons of concern.

By partnering with local and global institutions, UNHCR can provide refugees with a high-quality and culturally-sensitive education.

5. Scale solutions

Building a network to facilitate connected learning on a global scale

As consortium partners deepen their engagement in connected learning activities, they are also looking for new collaborators and donors — including those from the global south — to step up. The majority of funding today comes from northern donors whose standards are based on northern teaching and class policies, which can complicate programs that require significant structural flexibility.

Collaborations with the private sector, in particular, are seen as promising ways to generate cost-effective business models for the delivery of connected learning. Imagine, for instance, a learning center that is used as a revenue-generating Internet cafe during the evenings.

Outsourcing the running of computer labs, or making use of available ICT centers or cyber cafes, on the other hand, may assist with the care, maintenance and cost of these centers. And crowdsourcing the maintenance of sites or development of materials — including translations — could prove a cost-effective way to develop innovative and diverse content.

For UNHCR, engaging in the consortium is as much about connecting connected learning actors that have traditionally worked largely in isolation, as it is to transition from a somewhat limited role as a scholarship administrator into a facilitator of access to higher education on a grand scale.