Sudanese refugees seek safety in troubled South Sudan

News Stories, 28 December 2015

AJUONG THOK, South Sudan, Dec 28 (UNHCR) – Through the cracked windows of the bus, Amal Bakith's children watched the unfamiliar landscape roll by. Flat wetlands where cattle grazed and herons stalked swampfish; villages of domed homes with high thatch roofs; distant shady groves of acacia trees.

It was a kind of paradise, compared to the Sudanese homeland they left a week earlier, where the fighting meant their mother, a farmer, was unable to grow food to feed them. Previously a bomb dropped from a low-flying aircraft had paralysed their grandfather and driven their father to the frontline to fight back.

"Where we are going, we will have a better life," said Bakith's 11-year-old daughter, Fayais. Squeezed beside her on the tattered bus seat, her brother, Damar, six, said simply, "And we can go to school."

Bakith and her family were among 31 Sudanese refugees on their way to a new settlement in neighbouring South Sudan, the world's youngest nation that was itself thrown back into conflict two years ago after months of political tensions erupted into violence.

A peace agreement in August 2015 that was supposed to end that fighting has been repeatedly violated, its future now fragile. Nonetheless, the government in Juba has opened its arms to those fleeing four years of conflict in Sudan, its neighbour to the north, setting aside land to settle tens of thousands of refugees.

The violence they are fleeing, between the Sudan government and opposition forces in the Nuba Mountains and South Kordofan regions, usually flares at the end of the year, when the rains end. For people like Bakith, it felt like time was running out to escape before the bombs came again.

"Our houses were destroyed. Our farms were destroyed," Bakith said in a video interview as the bus headed south away from the borderlands. "We couldn't plant food for ourselves. We had to hide in caves to avoid the bombings."

Her valuables had long ago been bartered for food. With her husband away fighting, she had no help raising the children, none of whom had seen the inside of a classroom in years.

Then, a year ago, a bomb dropped from a low-flying aircraft exploded near her home, driving white-hot shrapnel through her elderly father's body, shattering his pelvis and paralysing him from the chest down.

"We planned since then to leave," Bakith said. "We decided that I would come with the children. It was hard to leave my father, but I promised him I would go back for him soon."

The walk to safety took a week. At times, Bakith left her eldest daughter by the road watching her brother, while she walked ahead with the baby and another son. After an hour, she left them in the care of strangers and doubled back to fetch her other children. This went on for two days. "I cried to God to help me with strength," Bakith says, her eyes downcast.

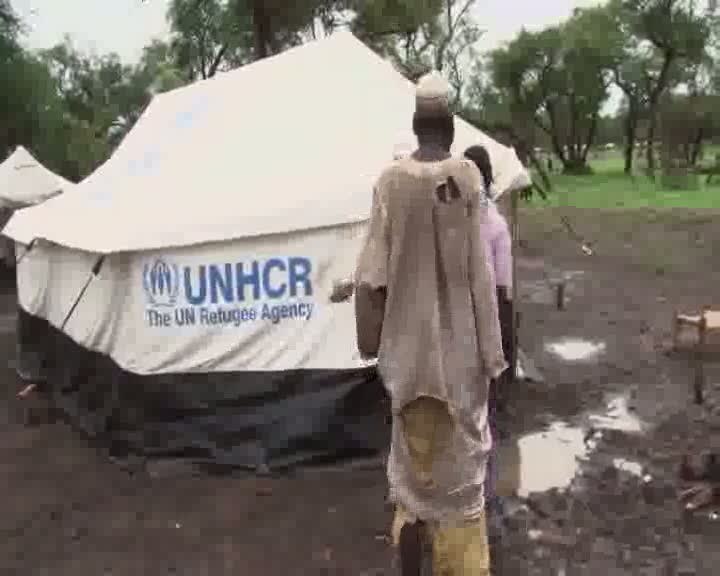

But eventually they arrived to Yida, a town just over the border in South Sudan, where UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, gathered the family together and transferred them to the bus to Ajuong Thok.

Less than two hours after arriving there, UNHCR and its partners had given Bakith and her family plastic sheeting and poles to build a temporary home, cooking pots and pans, mosquito nets, blankets, sleeping mats, and food.

By the next afternoon, they had their new land, roughly 150 square metres not far from a water point, a stick-and-thatch church, and a sports ground where children chased after a makeshift football. Soon, their new home was built. "They could not believe how big it was, they were very excited," Bakith said with a wide smile.

Ajuong Thok is today expanding into a large town, with the aid of UNHCR and its partners led by the Danish Refugee Council. Already, 31,000 refugees live here. Another 19,000 more are expected to arrive during 2016, some coming from a large unplanned refugee camp at Yida that is slowly being emptied.

In Ajuong Thok, refugees are housed on large blocks of land with services including water supplies and markets. There are kindergartens, three primary schools, and a secondary school. Food distributions take place monthly.

But resources are stretched. Recently, the World Food Programme had to reduce rations by 30 percent. The rudimentary clinic needs more medicines. Classrooms are already full.

"Now that the rainy season has finished, we are expecting a lot more people to come," said Rose Mwebi, a UNHCR protection officer in Ajuong Thok. "We are able to give them basic material like shelters and kitchen sets, but it is very limited assistance. We are still in an emergency situation here, and there are very many gaps."

Bakith was relieved to be safe, but she was quick to point out that things were still difficult. Hajir, her year-old baby daughter, was being treated for malaria. Hamed, her youngest son, showed similar symptoms. All of the children still wore tattered clothes, and their food would have to last almost three weeks until the next distribution. She had no money, and knew next to no-one at the camp.

A short distance away, Ibrahim Ali, one of her neighbours, who arrived to Ajuong Thok two years earlier, sat sharing an evening meal with friends.

"I remember, it is not easy when you first arrive," he said. "But I would advise her: be patient. There is still hunger, and things are hard, yes. But when I came here I could not read or write, and now I can. In time you will see your children educated, and even yourself.

"At home there is no food and no school, and there is the risk of bombing. If you are patient, you will see this place cannot compare with there, and you will see the benefits of staying."

Written by Mike Pflanz in Ajuong Thok, South Sudan