World Refugee Survey 2008 - Angola

| Publisher | United States Committee for Refugees and Immigrants |

| Publication Date | 19 June 2008 |

| Cite as | United States Committee for Refugees and Immigrants, World Refugee Survey 2008 - Angola, 19 June 2008, available at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/485f50c0c.html [accessed 5 November 2019] |

| Disclaimer | This is not a UNHCR publication. UNHCR is not responsible for, nor does it necessarily endorse, its content. Any views expressed are solely those of the author or publisher and do not necessarily reflect those of UNHCR, the United Nations or its Member States. |

Introduction

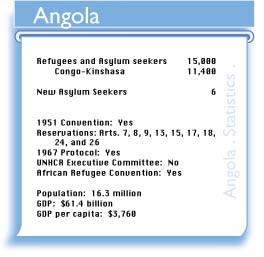

Angola hosted about 12,100 refugees and 2,900 asylum seekers at year's end. The largest group of refugees was 11,400 from the Democratic Republic of Congo (Congo-Kinshasa), who mostly arrived in the 1970s. It is likely there were more refugees among the estimated 400,000 Congolese living in northern Angola, but there had never been a complete formal registration and births and deaths often went unrecorded. Around 7,000 Congolese refugees continued to live in Viana camp, most born to parents who fled Congo-Kinshasa (then Zaire) in the 1960s. In March, six Eritrean soccer players requested asylum following their team's loss to Angola. A small number of Iraqis arrived during the year.

Refoulement/Physical Protection

In February, Angolan officials sent an Ivorian refugee to the airport, preparing to refoule him, but the Office of the UN High Commissioner (UNHCR) successfully intervened to prevent his deportation.

The Government deported tens of thousands of individuals during the year from different diamond mining areas of the country, many of whom Angolan soldiers mistreated. UNHCR obtained assurances from the Government that no refugees were among the deportees, but government forces likely expelled some refugees and turned asylum seekers back at the border.

During the year, Angola deported 44,000 Congolese from Luanda Norte. In Luanda Norte, the northern diamond mining region, Angolan soldiers systematically beat, tortured, and raped hundreds of Congolese migrants before deporting them across the border to Congo-Kinshasa in December, exposing some to HIV and others to sexually transmitted diseases. Reportedly, soldiers packed migrants into trucks without food and water and threw the corpses of those who died of starvation en route into the bush.

In the Maludi and Luaku diamond mining areas, in July, Angola detained and expelled 12,000 foreigners whom it considered illegal economic immigrants, including women and children. Many long-term Congolese refugees lived in this area, along with refugees and asylum seekers from other nations, and many supported themselves by mining illegally. Those expelled came from Mali, Equatorial Guinea, Guinea Bissau, Cameroon, Liberia, Congo-Kinshasa, the Republic of Congo, Côte d'Ivoire, and Nigeria. UNHCR had no access to most deportees, but, along with the International Organization for Migration, it monitored the entry of potential asylum seekers among the mixed migration flows.

In March, UNHCR began but could not complete a comprehensive formal registration exercise of all refugees and asylum seekers in Angola, which it hoped to attempt again in 2008. In November, the Social Welfare Ministry sponsored a three-day seminar on refugee rights and on the reception of and policy toward asylum seekers.

Angola was party to the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees (1951 Convention), its 1967 Protocol, and the 1969 Convention governing the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa (1969 Convention). It maintained reservations to the Protocol's dispute resolution provision and the 1951 Convention's right to work and reserved the right to restrict refugees' freedom of movement and residence. Angola's 1990 Law on Refugee Status provided for asylum based on the 1951 and 1969 Conventions. However, the law contained only general provisions, and implementing agencies lacked both detailed regulations and funding for asylum processing. UNHCR participated in an ongoing revision process and helped draft a revised document, which remained under Government review. The Government granted citizenship to an undetermined number of Congolese refugees in the provinces but not in politically sensitive urban areas like Luanda.

During the year, Angola's Committee for the Recognition of Asylum Rights (COREDA), the government body that conducted refugee status determinations, ruled on 138 asylum requests, of which it granted 79. Although the Law on Refugee Status did not explicitly provide for appeals, COREDA informally allowed appeals of its decisions, which it heard. As refugee status determinations were administrative decisions, rejected asylum seekers could also appeal to the courts, although few did because of the poor state of the Angolan judicial system.

Detention/Access to Courts

There were several instances of the Government detaining refugees and asylum seekers during 2007 as part of its campaign against illegal immigration. The Government detained the six Eritrean soccer players before assessing their asylum claims.

Angola had a temporary center at Luanda airport, where it held foreigners whom it did not permit to enter the country. As of March 2008, the center housed five people from Somalia, including a female head of household and two female children, who arrived without visas and whose situation UNHCR was assessing. In November,the UN Special Rapporteur on Religious Freedom inspected with UNHCR the new detention center at Viana, which, although still under construction, already housed 165 detainees from countries including Sierra Leone, Côte d'Ivoire, Iraq, and Zimbabwe, most of whom authorities arrested in diamond mining areas without proper documentation.

UNHCR, the Legal Assistance and Reintegration Centre (LARC), and local and international NGOs had to obtain previous authorization from the Ministry of Interior (MOI) to visit detention facilities. Jesuit Refugee Service (JRS), UNHCR's implementing partner, operated one LARC office in Luanda and opened another in Moxico Province mid-year. Together they assisted 3,149 refugees in obtaining documentation and provided legal aid to detainees. Refugees could not use the courts to vindicate their rights.

Recognized refugees received free COREDA-issued identification cards, which were of poor quality and easily forged. Because the MOI, which regulated foreign residents in Angola, did not issue the cards, authorities rejected them and often harassed and imprisoned holders.

Freedom of Movement and Residence

Asylum seekers and refugees could live where they chose, provided they notified authorities of their address. UNHCR helped the Government administer Viana and Sungui settlements for Congolese refugees.

Asylum seekers had to obtain authorization to travel between provinces and the lack of adequate documentation made it difficult for refugees to travel freely within Angola. Police frequently harassed and extorted money from travelers, not specifically targeting refugees but affecting them, and restricted access to diamond-rich areas.

Angola's 1994 Law on the Legal Regime of Foreigners granted foreigners freedom of movement and residence, subject to security restrictions imposed by the MOI. Regulations required refugees to obtain permits to travel in restricted areas, unless it was part of their normal travel between home and work.

The Law on Refugee Status entitled refugees to international travel documents, valid for two years and renewable in Angola or at Angolan consulates. Between September 2006 and July 2007, UNCHR issued 142 such documents.

Right to Earn a Livelihood

While the Law on Refugee Status stated that refugees "shall be entitled to engage in gainful activities," very few refugees were able to do so in the formal sector. Typically, UNHCR had to intervene to help refugees gain access to formal employment, as many employers, as well as immigration officials, did not recognize the cards issued by COREDA as valid for employment.

Many long-term Congolese refugees were unable to work formally because they lacked documentation. Refugees did not enjoy the protection of Angolan labor legislation, as most worked informally. The Development Workshop (DW), an international NGO, dispensed microcredit assistance to refugees who operated small businesses and traded agricultural products. Refugees could not legally run businesses, and could not open bank accounts because banks did not accept refugee cards. In September, help from JRS and LARC resulted in the authorities issuing the first commercial permit to a refugee.

Public Relief and Education

The Government funded only the administrative aspects of refugee protection, with no separate funds for assistance. UNHCR and its partners helped refugees gain access to public services in and around the capital, Luanda. A few hundred of the neediest refugees in Luanda received food aid from UNHCR. Outside the capital and its surroundings, UNHCR did not provide assistance, focusing 75 percent of its efforts instead on reintegration of returning Angolan refugees.

Following UNHCR's 2005 handover of the schools in Viana refugee camp to Angola, both Angolan and refugee children attended them. Nearly 800 refugee children attended Aksanti School in Viana, which offered education through grade four, as did those in the Sungui settlement in Bengo Province, with nearly 100 refugee students. Many refugee children did not continue past grade four because the national schools charged high fees and discriminated against them for their lack of documentation. Fewer than 20 refugees attended postsecondary schools.

Most international financial institutions included only Angolan refugee returnees in their development plans for the country, except for DW, which ran a micro-enterprise program for refugees.

USCRI Reports

- Africa: Nearly 2 Million Uprooted by New Violence in 19 African Countries Last Year (Press Releases)

- Africa: New Displacement of Nearly 3 Million Africans Largely Unnoticed by Rest of World (Press Releases)

- Refugee Return to War-Devastated Angola (Press Releases)