World Refugee Survey 2008 - Lebanon

| Publisher | United States Committee for Refugees and Immigrants |

| Publication Date | 19 June 2008 |

| Cite as | United States Committee for Refugees and Immigrants, World Refugee Survey 2008 - Lebanon, 19 June 2008, available at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/485f50c076.html [accessed 5 November 2019] |

| Disclaimer | This is not a UNHCR publication. UNHCR is not responsible for, nor does it necessarily endorse, its content. Any views expressed are solely those of the author or publisher and do not necessarily reflect those of UNHCR, the United Nations or its Member States. |

Introduction

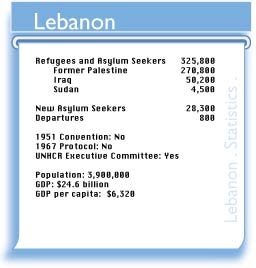

Lebanon hosted about 325,800 refugees and asylum seekers, including some 270,800 Palestinians who arrived after the 1948 creation of Israel, and over 50,000 non-Palestinians from the Middle East and Africa. The UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) had registered roughly 411,000 Palestinian refugees, but this figure included many who had acquired Lebanese citizenship or resided outside Lebanon. Most Palestinian refugees lived in 12 refugee camps and in informal settlements throughout the country.

The number of Iraqis more than doubled to 50,200, in part because of violence in Iraq and insecurity in Syria. The Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) registered around 9,800 Iraqis and referred nearly 1,500 for resettlement but many did not register.

There were about 4,500 mostly unrecognized Sudanese refugees and asylum seekers in the country and about 340 registered with UNHCR.

Refoulement/Physical Protection

Lebanon forcibly returned more than 300 refugees and asylum seekers detained for illegal entry or stay, including more than 200 Iraqis. While the Government claimed they returned voluntarily, their choice was between repatriation and indefinite detention. Authorities did not allow independent monitoring of returns and did not regularly inform UNHCR in advance. Authorities expelled one family of four with refugee status to the Syrian border despite UNHCR's request for their release. A father and son who had registered with UNHCR allegedly chose to repatriate to Iraq, but the son returned to Lebanon after the father's killing and his own detention.

By June, the International Organization for Migration (IOM), in cooperation with the Iraqi Embassy, had returned 75 Iraqis, 70 of whom were in detention for illegal status. In September, IOM suspended its participation in the operation but also indicated that it might resume later.

The Sudanese Embassy reportedly visited Sudanese detainees in prison in preparation to return them to Sudan.

From May to September, fighting between the Lebanese Armed Forces and the militant group Fatah al Islam (FAI) at Nahr al Bared Palestinian refugee camp in the north left 168 soldiers and 42 civilians dead. The fighting later spread to Ein al Hilweh camp. The army used heavy weapons disproportionately during the conflict and shelled the camp indiscriminately after its evacuation. The conflict displaced over 32,000 refugees from the camp and surrounding areas. In June, Lebanese security forces killed three Palestinian demonstrators and injured about 50 more, as protesters pushed through a military checkpoint to Nahr al Bared. Security forces shot into the air, the crowd began throwing rocks and sticks, and the soldiers opened fire upon them with automatic weapons. Lebanese soldiers reportedly tortured some who fled the camp. A nurse at Beddawi camp clinic reported seeing 30 cases of abuse. One refugee reported the army detained him at the Kobbeh military base for two days before transporting him to what he believed was the Ministry of Defense in Beirut. Prison officials accused him of belonging to FAI, kept him blindfolded in a crowded prison cell for eight days, beat him, and "twist[ed] his extremities almost to the point where he lost consciousness."

Lebanon was not party to the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees or its 1967 Protocol, and did not have a functioning refugee law in accord with international standards. The 1962 Entry and Exit Law prohibited refoulement of "political refugees" and provided that any foreigner whose life or liberty was in danger for political reasons could seek asylum. In theory, an inter-ministerial committee headed by the Minister of Interior (MOI) would handle political asylum cases, but few applied for asylum and the Government granted political asylum in only one known case in 2000 to a member of the Japanese Red Army. Lebanon's 2003 Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with UNHCR declared that "Lebanon does not consider itself an asylum country" and, under its mandate, UNHCR carried out all refugee status determinations.

The MOU covered only refugees who entered the country after it went into effect and precluded persons already in the country legally from applying. It also did not cover Iraqis under UNHCR's temporary protection regime. Lebanon permitted asylum seekers and refugees to remain on the condition that UNHCR repatriate or resettle them. Of those who entered illegally, the MOU covered only those who applied for asylum with UNHCR within two months of entry. A 2006 Ministry of Justice advisory generally affirmed that the Government should not return refugees recognized by UNHCR. UNHCR had three months to make status determinations and had to hand in the list of names of rejected applicants to the Directorate General of the General Security (GSO). If UNHCR granted refugee status, the MOU gave UNHCR six months to find countries to accept the refugees for resettlement. During this time, the Government issued circulation permits, which it renewed only once "for a final period of three months after which time the General Security would be entitled to take the appropriate legal measures." UNHCR rarely was able to complete registration, status determination, and resettlement within a year.

In February, UNHCR began granting all Iraqis from central and southern Iraq prima facie recognition unless they fell under one of the 1951 Convention's exclusion clauses and did not register them under the MOU as it did other refugees.

A 1962 decree recognized most Palestinians as "foreigners without identity documents from their countries of origin residing in Lebanon on the basis of residence cards issued by the GSO or by the General Directorate of the Administration of Palestinian Refugee Affairs [renamed the Directorate of Political Affairs and Refugees in 2000 (DAPR)]." Those whose families fled after 1948 or whose first country of exile was not Lebanon generally could not register.

Detention/Access to Courts

Between January and April, there were 150 to 200 refugees and asylum seekers in detention. By November, detentions reached their peak and there were reportedly more than 1,200 foreigners in arbitrary detention, including 760 in Internal Security Forces (ISF) prisons and nearly 500 in GSO centers, most of whom were Iraqis. Some 800 detainees were refugees and asylum seekers, 90 percent of whom authorities detained for illegal entry or stay.

Lebanon's regulations stated that prison authorities should refer foreign detainees who had completed their sentence to the GSO, which would then decide to deport or release them. Instead, authorities gave them the option of remaining in prison or returning to their countries of origin.

Soldiers arrested and detained Palestinians including one from Nahr al Bared for four days, during which they punched and slapped him and gave him food only twice. Members of some Palestinian groups who controlled camps also reportedly detained rivals during territorial clashes.

Lebanon's prison conditions did not meet international standards and medical services remained insufficient. There were at least seven reported deaths in detention centers, due to inadequate medical services and torture. In September, a Sudanese man detained in Jbeil for illegal entry died of a heart attack following his transfer to a hospital. In August, three detainees in Rumieh prison died, including a Palestinian accused of FAI membership. Family members reported that he did not receive medical attention despite a gunshot wound he sustained in the Nahr al Bared fighting.

The Government kept most detainees for illegal entry at the overcrowded Rumieh prison. Although it had a capacity of 1,500 to 2,000 people, it held between 2,000 and 3,000, some who had already served their sentences. Overcrowding led to violence between refugees and Lebanese prisoners, including serious cases in August and December.

In February 2008, under an ad hoc arrangement between the Government and UNHCR, the GSO gave Iraqis who had entered the country illegally or overstayed their visas three months to regularize their status, the same period it granted illegal migrants. After UNHCR paid their fines for illegal entry, £L951,300 (about $630) each, GSO released 155 Iraqi detainees in the month following the agreement. To legalize, Iraqis not enrolled in school or those who did not have a Lebanese spouse or parent would have to find sponsors, obtain work authorizations, pay $300 residency fees, present proof that a sponsor had paid a $1,000 bank deposit on their behalf, and pay for medical tests and insurance.

The 1926 Constitution, amended in 1990, assured protection from arbitrary arrest, imprisonment, and custody to all persons. The 1962 Entry and Exit Law provided that GSO would issue special identity cards to political refugees. The 2003 MOU provided that the GSO would notify UNHCR of asylum seekers detained "at its premises" and UNHCR could send "an explanatory letter with the proper documents" if it wished to interview other detainees. Authorities released refugees from detention when UNHCR intervened if they had resettlement prospects. If not, the Government detained them indefinitely beyond the initial imprisonment sentence, without judicial review. UNHCR and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) had access to detained refugees and asylum seekers.

Although refugees and asylum seekers technically had access to courts, those without status avoided them. Lebanon granted immigration hearings to dozens at a time, during which the judge called on them to respond to questions about the legality of their entry or stay by raising their hands or nodding. In criminal proceedings, Lebanon provided legal aid to foreigners whose home country provided the same to Lebanese nationals, which excluded all Palestinians. UNHCR provided legal aid for 136 cases, mostly involving illegal entry and stay, while others involved arbitrary detention, criminal offences, and civil law cases. In at least two cases, the court dropped charges of illegal entry against UNHCR-recognized Iraqi refugees.

Freedom of Movement and Residence

During the conflict in Nahr al Bared camp, the Lebanese army forced some 30,000 Palestinian refugees to relocate. The majority moved either to Beddawi camp in the north, to schools set up by UNRWA, or to relatives in other camps. In November, the military allowed about 1,800 families to return to a section of the camp on the periphery but sealed off the center.

Most non-Palestinian refugees could not move freely within the country for fear of arrest. The Government restricted movement mostly at checkpoints, where many police and military officials did not respect UNHCR documents, especially after the conflict in Nahr al Bared.

Under the MOU, GSO issued 52 circulation permits to non-Palestinian refugees and asylum seekers who entered illegally pending UNHCR's determination of their status. More than 400, however, were eligible for them but did not receive them. The Government could also issue circulation permits pending resettlement, which it renewed only once for a maximum of 12 months. UNHCR no longer requested circulation permits from GSO for those Iraqis it recognized prima facie. It gave them refugee certificates but these did not afford the same benefits and did not exempt bearers from penalties for illegal presence.

The Government gave all UNRWA-registered Palestinian refugees and their descendents renewable five-year travel documents. Palestinian refugees registered with DAPR received travel documents valid for one year. In 2006, GSO stated that refugees who obtained foreign passports could still keep their travel documents.

The Government did not issue international travel documents to non-Palestinian refugees except for resettlement.

Right to Earn a Livelihood

In general, Lebanon did not allow refugees to work legally. Many joined the informal black market as unskilled laborers. Women and adolescent children often provided for families in illegal status as they were at less risk for arrest. While domestic labor legislation existed, most refugees could not use it for fear of arrest. Under Lebanese law, courts could sentence anyone who entered the country and worked illegally to at least one month in jail and a fine.

Non-Palestinian refugees in the country legally had to apply to the Ministry of Labor (MOL) for work permits as foreigners. They had to be experts or professionals in a field where no Lebanese candidates were available, to be residents of Lebanon since 1954, or to work in a company for at least nine consecutive months during the year. Professions practiced through association, such as medicine, law, and accounting, were open only to Lebanese with few exceptions. Lebanon also offered work permits to foreigners married to Lebanese women for at least a year or to those who had Lebanese mothers or were of Lebanese descent.

From March to June, refugees and asylum seekers with employer-sponsors and work permits could regularize their status, but only to that of migrant workers and they also had to withdraw their asylum applications or refugee status. It did not extend legal status to family members and there was no assurance of renewal.

In 2005, the MOL partially repealed restrictions prohibiting Palestinian refugees from working in 70 types of jobs. The edict covered about two-thirds of the occupations previously restricted, generally the low- to medium-skilled ones. To obtain a work permit, a Palestinian had to have been born in Lebanon, have registered with the MOI, and have a contract with a specific employer. Annual fees for work permits ranged from £L240,000 (about $160) for workers earning below the minimum wage of £L300,000 (about $200) per month to £L960,000 (about $640) for workers earning twice the minimum and £L1,800,000 (about $1,205) for consultants, experts, general directors, or heads of accounts. Registered Palestinians had to pay only a fourth of those fees, but were ineligible for social security because of a requirement that foreigners' home states give reciprocal benefits to Lebanese: since the Palestinians had no home state they were automatically ineligible but still had to contribute to it. The edict did not change a 1964 law that also imposed a reciprocity condition on membership in professional syndicates – a precondition for employment in professions such as law, medicine, engineering, and journalism – which also effectively excluded Palestinians.

Few Palestinians received work permits and, if they did, it was normally for unskilled employment. Many worked illegally, especially in construction and agriculture.

The amended Constitution of 1926 promised protection of property rights to all. Foreigners, including refugees, could own limited plots of land but they had to fulfill special legal requirements, including the approval of five different district offices. An amendment made in 2001 to the Property decree of 1969 allowed foreigners to acquire property only if they came from countries that granted reciprocal rights to Lebanese. This excluded Palestinians from acquiring or bequeathing property to their heirs. Banks required nonresident foreigners to have a valid entry visa to open an account but refugees could register vehicles in their names at the MOI.

Public Relief and Education

Palestinians in Nahr al Bared did not have running water, sewage, or electricity for weeks during the conflict and health clinics were not operational. Lebanon had the highest percentage of Palestinian refugees living in abject poverty and the worst was inside the 12 camps. Some 5,000 non-ID Palestinians were not eligible for its assistance and reportedly could not graduate from secondary school.

There were no reports that the Government restricted humanitarian agencies' access to refugees, but there was no public assistance for refugees. FAI attacked the staff of international humanitarian agencies that tried to enter the camp. In May, FAI's attack against a UN aid convoy resulted in the death of two Palestinian refugees. The 2003 MOU required UNHCR to provide "the necessary assistance" to refugees holding circulation permits to avoid their being "a burden on the Lebanese Government." Palestinian refugees were not eligible for Government health services or education but UNRWA ran 25 health clinics.

A 1999 Ministry of Education decree granted all refugee children access to primary and secondary schools if space was available. The schools required all refugee children to have identification certificates issued by UNHCR. UNHCR and its partners provided educational grants to refugee families with primary school-aged children. Only around 10,000 Palestinian refugee children enrolled in either private or public elementary and secondary schools. UNHCR aided non-Palestinian refugee children in primary and secondary schools. UNRWA ran about 86 schools for Palestinian refugees.

USCRI Reports

- Middle East: International Community Fails to Protect Palestinian Refugees; Iran Continues to Host World's Largest Refugee Population (Press Releases)