Stateless in Liberia

News Stories, 25 September 2015

This weekend the world meets to commit to the Sustainable Development Goals to end poverty, protect the planet and ensure prosperity for all. For 10 million stateless people worldwide this will continue to be a dream as long as they are denied the nationality of any country.

The West African State of Liberia is one of 27 countries in the world that has legislation denying women the right to pass on their nationality to their children in the same way as men. This means children born to non-Liberian fathers and Liberian mothers outside of Liberia can be stateless if the father does not manage to pass on his nationality.

The identification of a child's parents through official birth registration can be important to the parents' ability to pass on nationality. In a region with very low levels of birth registration (in West and Central Africa only 47% of the births are estimated to be registered; in Liberia this figure is of 4%), the risk of statelessness is high.

Liberia has a stateless population in large part due to the high numbers of women who fled the country during its civil wars from 1989 to 2003 and gave birth to children, during their time in exile, with foreigners.

In Liberia, this has left an estimated 4,000 children inside Liberia potentially stateless and nearly 3,200 children outside the country potentially stateless; but the number could be higher.

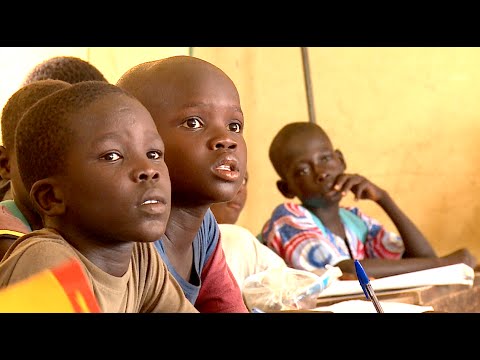

Without a nationality, many of these children cannot go to school, receive medical care or travel freely outside of the country.

Their only chance of acquiring a nationality in Liberia is to wait until they are 18 years old (and before 23 years old) to be naturalized. This naturalization process costs $175 per person, which is far too expensive for many in a population that earns, on average, US $1.25-2 per day. Left without hope, they have few opportunities to live a normal childhood.

This is a story about Georgia Gage, a 36-year-old Liberian widow, and her three children who do not have a nationality.

Georgia is a Liberian mother. Her children were born in Nigeria to a Nigerian father, who died when they were young. None of them have birth certificates or any other official documentation of their birth, which has prevented them from gaining Nigerian nationality.

Georgia has tried to get her children officially recognised as Liberian nationals but this has proven challenging. Liberia recognises children of "negro descent" born in Liberia and subject to the jurisdiction to be Liberian citizens. Liberia does grant people nationality without birth certificates. They, however, can only do this if the father is Liberian or if he has lived in Liberia for some time.

Georgia's children were born in Nigeria and their father is not Liberian.

This means Georgia's children are stateless.

"Something needs to be done for Liberian mothers who have kids with foreign fathers. It's my right to give my nationality to them, but I am not allowed to…

"I feel so bad and disappointed that I cannot protect my children. Liberian nationality law does not allow me to protect my children like a hen protects her chicks from the hawks".

Georgia and her family were living in Liberia, and her Nigerian husband was a merchant travelling regularly between Liberia and Nigeria. When he was killed during the civil war in Liberia, Georgia and her children fled to live with his family in Nigeria hoping to find safety. Unfortunately they became abusive towards her and so she returned to Liberia.

"This paper here is the only identity document I have to show. It was made in a refugee camp in Nigeria before we were repatriated to Liberia."

Georgia's situation was similar to her children's. With a Liberian mother and a Sierra Leonean father, Georgia too encountered problems when trying to acquire a nationality. Her only option was to naturalize when she turned 18.

"My kids are Liberian because their mother is Liberian. But the Liberian nationality law is not gender-friendly. It's all about he, he, he – never she…

"I had a lot of difficulty to obtain a passport and now my kids face the same problem. I had to naturalize; it cost me $175 to get the document I needed, before being able to acquire a passport. But I cannot afford to naturalize my children and I worry about their future."

Emelda, 17, Georgia's eldest has been unable to obtain any documentation all her life due to her inability to prove her nationality. As a result, she is unable to travel freely outside of the country. Now she worries that she won't be able to pursue her dreams and fulfil her potential, only because she is stateless.

"I want to become a lawyer. I look around me and see things that I want to change. But without a nationality it will be very difficult for me to pursue this dream. If I enrol at university they will immediately ask me for my papers, which I do not have".

Stella, 12, Georgia's youngest, sits on the bed she shares with her two siblings and mother. She was born in Nigeria but was never registered; now living in Liberia she cannot prove ties to either country.

"If I had the opportunity to naturalize now, I would do it. I don't think it's fair that I have to wait until I'm 18. I feel at home here".

Solomon, 14, plays with kite in the neighbourhood where he currently lives.

Georgia's son Solomon has had to face discrimination as a result of being stateless.

"My classmates tell me to shut up because I'm not from here. I don't talk much anymore in class because I know they'll make fun of me".

Georgia encourages her daughters to be strong and resilient.

"Because they don't have a nationality, they face a lot of problems in school and with their friends. They feel so bullied and are always put to shame", said Georgia.

"If the situation doesn't change they will continue to be invisible here. I should have the right to give them my nationality so they can feel like they belong."

To find out more about how you can join UNHCR's #IBelong Campaign to End Statelessness go to www.unhcr.org/ibelong