- Text size

|

|  |

|  |

|

- Français

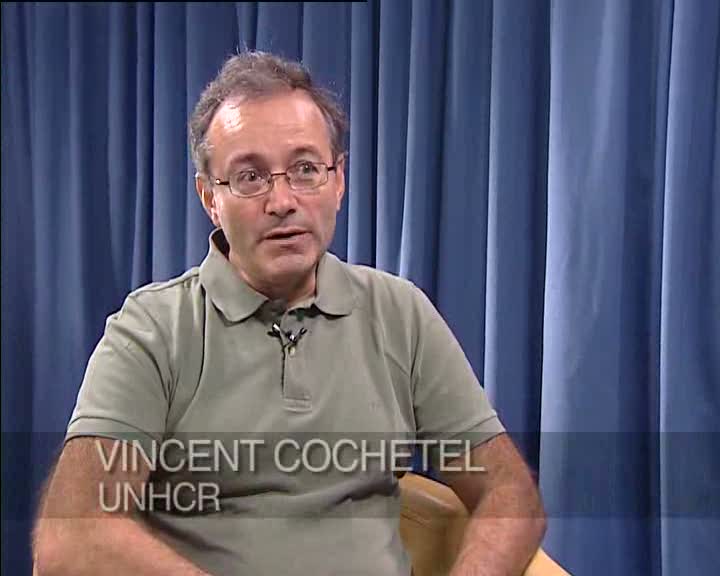

Q&A: "You have to find resources within yourself to cope with it."

News Stories, 19 August 2010

GENEVA, Switzerland, August 19 (UNHCR) – On a January night in 1998, Vincent Cochetel, then head of UNHCR's Vladikavkaz office in the North Caucasus, arrived at his apartment at the end of a days' work to find armed men waiting inside. Cochetel was forced to kneel on the floor with a gun to his neck. "I thought it was some kind of contract killing," he says. Beginning that night, and for 317 days, he was held hostage, often chained to a metal bed frame and confined alone in the dark. His experience underscores the risks humanitarian workers everywhere face in the course of their duties, and why they do it. On the occasion of World Humanitarian Day, UNHCR's Head of Media, Adrian Edwards, spoke to Cochetel. Excerpts from the interview:

Can you describe how it started?

We [were living] in secure flats, meaning many different locks, panic buttons at the entrance door and all that. I tried to open my door, and there were three guys waiting for me there with balaclavas, handguns with silencers. They took the key and they took control over the situation. The bodyguard could not do anything. I mean, if he had done anything we would have both been killed.

Vincent Cochetel interview

On the occasion of World Humanitarian Day 2010, a senior UNHCR staff member reflects on his experience being kidnapped near Chechnya in 1998.They took us inside the flat and separated us. They asked me to kneel down, put a gun into my neck. I felt the cold metal. I thought that was it. I thought it was some sort of contract killing because there you have that sort of thing happening in that part of the world. And I could hear the sound of, in the other room, of the bodyguard being bundled with tape. They beat him a bit. And after some long minutes they searched me, handcuffed me in the back. They blindfolded me. And we went downstairs, six floors. I fell a couple of times. [They] pushed me in the staircase, downwards. Then they put me in the trunk of the car. And then I was transferred from car to car for three days. I spent three days in the trunk of cars. Three days before being transferred to Chechnya.

You were kept alone, if I understand right, for much of the time of your captivity. What in general were the conditions that you were in?

Except for the first three days, I was in a cellar. A dark cellar, handcuffed, one hand to a metallic frame of a bed, and about 10-15 minutes light a day for meal.

And remind us, how many days?

For more than 300 days. The most difficult thing to describe is the sort of depths of loneliness you go through. Because there is nothing happening in the darkness. And to describe that is difficult because it's 15 minutes of light, the rest is… you're just alone by yourself. You try not to think too much, because otherwise you'll get crazy, but you have to keep your mind busy. To keep your mind busy, there's all sorts of games and activities. And you try to keep your body busy too.

Was there violence towards you during your captivity?

The first 12 days there was violence aimed at extracting information. So, 45 minutes of interrogation with loud music to cover the noise. And then it stopped. It stopped in an interesting manner. I'd like to describe that moment because for me I learned a lot through that period.

There was a guy interrogating me called 'Ruslan', a very violent man often under the influence of alcohol – a very violent person. And the night, or the day, before ( at the beginning I had difficulty knowing whether it was night time or day time) I had heard noises over my head, kids crying and vomiting and people running back and forth.

I asked him before the interrogation started, I said 'Can I ask you a question, Ruslan?' He said 'Yes." I said: ' Is your son sick?' He looked at me in shock and said, 'Who told you that I had a son?' I said, 'I guess you have a son because I hear a baby crying, a young boy crying.' … 'Who's gone and told you I had a son?' and I said 'No, no one told me you had a son, I just figure out you had children and I know what it is to have sick children at home, and I figured he was about two or three years old.' And he said, 'who told you his age?' and I said 'nobody told me his age, I was just guessing,' and then he said 'yes, he's sick, he's vomiting, we don't know why he is vomiting.' And then we started discussing about the health of kids, how difficult it is to purchase medicines in Chechnya, where he could buy some in Ingushetia, which NGOs [non governmental organizations] are left in the region. And we talked for 45 minutes about health of children, education of children. And I never saw that man again. He never touched me again. That was the end of the interrogation phase.

For me the lesson I drew is that even the worst sort of individual you face in life, you still have to try to make the effort to pull the right string. If you make that effort, you reverse some of the power balance. But if you don't make that effort to try then you can't expect much. And for me that was a good lesson because I realized that eventually I would be able to use that tactic with some other guards. It worked with some, it did not work with others. But at least you have to make the effort of trying. But I didn't know at that time that violence is something that eventually you cope with because they had an interest to keep me somehow in shape or alive at least up to a point. Isolation, that's not something you are prepared for, because you have to find resources within yourself to cope with it.

What about yourself at that time. You had ample reason to question why you were working, why you'd come there to work for UNHCR, what you were doing there?

You go through a lot of existentialist moments. You question the rationale of what you were doing. But again looking back, if I had to do it again I think there was a good rationale for us to be there. We were feeding half a million people. We were restoring water supply to the entire republic, we were helping IDPs [internally displaced persons] to go back there, rebuilding schools, rebuilding social infrastructure, assisting people. We had good reasons to be there.

You were released, as I understand, on the Chechnya-Ingushetia border. What happened on that day?

I was taken out of bed very early in the night, put up against the wall, there was a bit of unnecessary brutality. Handcuffed in the back, taken into a car, and there was a whole convoy of cars, about five or six four-wheel-drive, brand new… armed guards all over the place. At some point I was taken out of the car, moved into another car. People wouldn't talk to me. Taken into another car where I'm forced to, to bend my head. There were four people in the car, with the car driving slowly off the road. I can feel it, that we're not on normal tracks. And then it was like we're in a bad movie, shooting all over the place. I feel a guy falling at me on the left, on the right there was no more guard on my right. So I dived out of the car and take cover at the rear of the car. There was shooting around. I can hear confusing orders in Russian and Chechen. And I'm asked to kneel again, which I hardly do, begging for mercy because I don't know what's going on basically. Four days before that four hostages were beheaded in another place, I knew about that and that there'd been some hostages been killed but you do not know the circumstances but I was aware of that. And then all of a sudden I am dragged by one or two guys, put in another car. They throw me like a bag of potatoes onto the floor of one of the cars. And then I had a helmet to my head when I was pushed into that car. When I felt the helmet I knew I was with regular forces. And then we drove and I was taken to a safe place.

You're still working with UNHCR. Why do you continue to work for an organization that has put your life at risk for your work, in which you could be subjected to risk again?

A couple of people asked that to me afterwards, saying, didn't you have enough? And, if I'd stopped working for UNHCR at that time, it would have meant they'd taken something away from me. Those guys would have won. It was very important for me to continue, prove myself that I was able to work, and that I was maybe able to make a personal difference somewhere for some refugees. A couple of years after I can say what I've gone through has brought me a bit closer to a refugees' experience. I didn't know what torture was. I didn't know what solitary confinement was, now I can talk about it, I can recognize those signals when refugees talk about it. So I think that makes me a better listener at least. If I can bring a little part of that experience back into the system through the training of my colleagues, training of other aid workers, or training of colleagues who interview refugees or asylum seekers, that can be a useful experience after all.

What did you learn about yourself?

Strengths, weaknesses. I know the thin line between madness and sanity. I've explored depths of loneliness that very few people have explored. But you find a way through things. That's the beauty about human nature.

And you still find it worthwhile to be a humanitarian worker, despite what you've been through?

Oh yes, because as long as you think that what you do can make a little difference then it's worth[while]. I've invested many years of my life in this organization, it could have been another organization, but I chose this one. I don't think that this year [1998] when I was away from the organization, in captivity was a useless year. I think I've learned a lot, and if I can share a bit of that experience with colleagues, that's added value for the whole office and colleagues who served in similarly dangerous places.